| Main Page - Back |

|

From SudokuWiki.org, the puzzle solver's site |

Introduction

Known and Unknown in Sudoku

A sudoku puzzle is one of the deepest logical objects discovered in recent decades or rather re-discovered, since it has been around from the time of Euler and for a while has existed independently among popular puzzles in Japan. Its true depth, however, has been realized only at start of 2005, when puzzle-solving minds had a chance to tackle high-quality examples published in newspapers in the West. Solvers have been motivated by a desire to impose a logical solution for any puzzle, but for every one felled with deft logic, more appear which defy any strategy. Are we ever going to arrive at a Grand Theory of Sudoku? This is still a great unknown. This website (formally book) will outline where we are and what we need to build on. By doing so, it will not only arm you with the tools to challenge any Sudoku you’ll find in a book or newspaper but also equip you to take on the unknown.

How Many Sudoku Puzzles Are There?

A popular question. Along with “Have I ever done the same puzzle twice?” Fortunately I can improve on the answers “many” and “unlikely” since mathematicians have sat up all night to answer this. But first, a diversion on how Sudoku puzzles are made. It is much easier to start with a completed or filled in Sudoku board – like a solution, and then take numbers away. Eventually you will take enough numbers away such that any further subtractions will cause the puzzle to have more than one solution. That is bad for the puzzle and frustrating to the puzzle solver, so we stop when that occurs and we have the new puzzle. It usually leaves between twenty and thirty clues behind. How easy that puzzle may be is a much more difficult question.

Now, your intuition will be correct in assuming there are many, many puzzles you could make from a filled in Sudoku board – because you can subtract any clues in any order. So the first question is: how many Sudoku solutions are there? Bertram Felgenhauer used a brute force computer search to find

Now, your intuition will be correct in assuming there are many, many puzzles you could make from a filled in Sudoku board – because you can subtract any clues in any order. So the first question is: how many Sudoku solutions are there? Bertram Felgenhauer used a brute force computer search to find

6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960

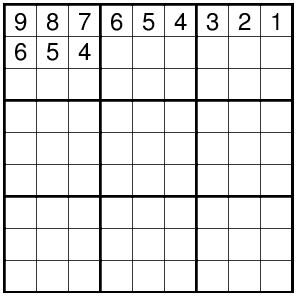

filled in Sudoku solutions. A whopping number! The very first one of these solutions will start, top row, with the numbers 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 and the very last puzzle will begin with 9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1.Sudoku Symmetries

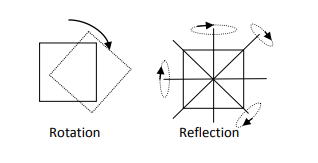

But are all these Sudokus really different? If we rotate a sudoku 90º, isn’t it really just the same sudoku? Yes, it will solve in the much same way, although it might be confusing to try it and you probably will solve it in a slightly different way with pen and paper. The Solver has rotation buttons just in case you want to try it.

We can also transpose the numbers – which means we can swap all the numbers 1 with 2, for example. Or shift the numbers up by one and make 9 equal to 1. There are nine numbers and in total 362,880 ways to arrange those nine numbers. So that immediately cuts down the number of unique puzzles. It is easy to forget that the numbers in Sudoku are merely placeholders. We could use types of fruit, coloured balloons or Portuguese irregular verbs equally well. Okay, not equally well...

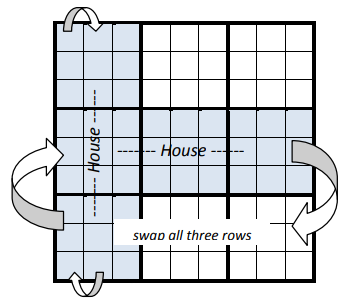

- Rows can be swapped with other rows and columns can be swapped with other columns provided that either

- the swapping occurs within the same house, or

- entire houses are swapped.

We can move the central three rows, for example, and swap them with the bottom three rows. This can mess up a symmetrical puzzle, but the solve route will be identical, so the puzzle will be essentially the same.

What this messing around boils down to is

5,472,730,538

unique grids from which a great number of puzzles can be made. So it is extremely unlikely you’ve ever done the same puzzle twice in two different places.What Is the Minimum Number of Clues?

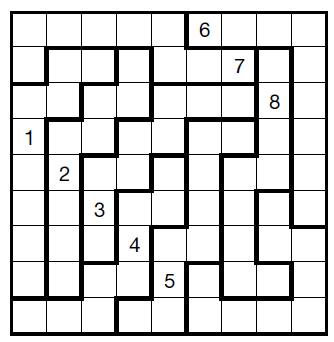

Jigsaw sudoku puzzles allow smaller clue sets to produce puzzles of the same grade. The minimum number of clues for a jigsaw has been computed to be eight, as in the example from www.bumblebeagle.org.

Such a puzzle can be solved without trial and error but is almost impossible to complete with just pen, paper and logic (currently)

The Solver has example of easy and hard 17 clue puzzles

A Puzzle in a Puzzle

This question speaks to the symmetries discussed above. Given all the ways the same board can be expressed, there should be one board with the lowest number - starting 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 in the top row. This is called the "base" number or the "normalised" board. If one were interested in detecting whether two boards or two puzzles were "essentially the same", transposing them to the normalised board would be the way to determine this, since you can compare the two numbers. If a reader has more information about an algorithm to do this, please add the comments below.

The Strategy Families is the next best page to read and after that Getting Started. This distinction between 'Brute Force' vs Logical Strategies is discussed here.