| Main Page - Back |

|

From SudokuWiki.org, the puzzle solver's site |

Avoidable Rectangles

Avoidable Rectangles are a most unusual strategy - and, to this author's knowledge, the only one that makes use of solved cells. We are used to the idea that a solution kills all the other numbers of the same value along the row, column and box, meaning that all information about that cell has been used up. Apparently, this is not so.

To appreciate this strategy, we have to put ourselves in the shoes of the puzzle creator, not the puzzle solver.

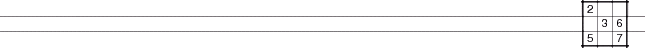

Consider the solution in diagram to the right. We have four cells that are shaded. To create a Sudoku puzzle, some removal process has to take place - some method of taking out numbers so that they can be filled in again by a puzzle solver. The crucial constraint is that the puzzle must have a unique solution. If the puzzle maker removed all four shaded cells, then there would be at least two solutions, since the 1 and the 2 are interchangeable in this situation.

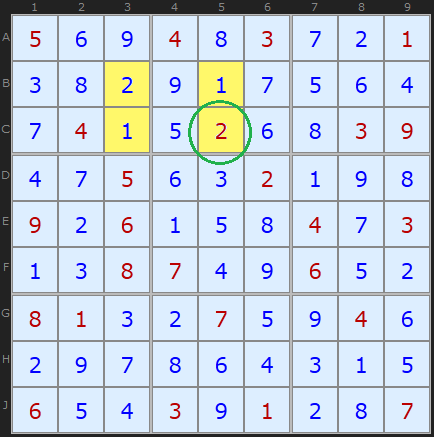

There are millions of possible puzzles derivable from a completed Sudoku board. The top third of the puzzle above is just one example. Notice, however, that at least one of the four cells (C5) from our example is a clue - which avoids creating a double solution.

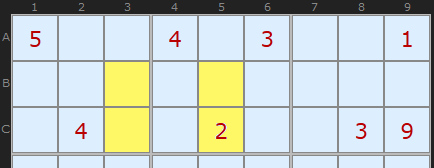

Work on the puzzle so far has fixed 5 in C4 and B7 and 8 in C7, but the final corner has two options ‑ an 8 or a 9. If B4 really were an 8, then we’d have the same situation as in the case of the 1 and 2 where the puzzle maker was forced to leave a clue. Since our newly identified rectangle does not contain a clue in the corners, we can’t have an interchangeable pair here. The 8 is not a valid solution, so we can remove it and place a 9 in B4.

So the rule of Avoidable Rectangles is:

We can remove a candidate that forms a potential interchangeable pair with three other cells spread over two boxes where the three other cells are solved cells (not clues).

Extensions of this strategies are documented in my book The Logic of Sudoku.

Note: This strategy does not exist in the solver because it relies on knowledge of what the original clues were. However, my solver is only given the state of the board as it currently exists and solved cells could be clues or cells solved in a previous round. It does not know. The data entry does allow one to distinguish between them but I can't force the user to abide by it.

So the rule of Avoidable Rectangles is:

We can remove a candidate that forms a potential interchangeable pair with three other cells spread over two boxes where the three other cells are solved cells (not clues).

Extensions of this strategies are documented in my book The Logic of Sudoku.

Note: This strategy does not exist in the solver because it relies on knowledge of what the original clues were. However, my solver is only given the state of the board as it currently exists and solved cells could be clues or cells solved in a previous round. It does not know. The data entry does allow one to distinguish between them but I can't force the user to abide by it.

Higher Order Avoidable Rectangles

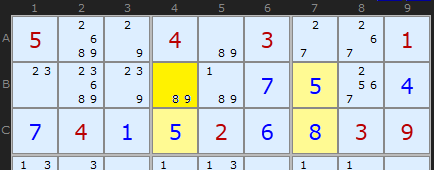

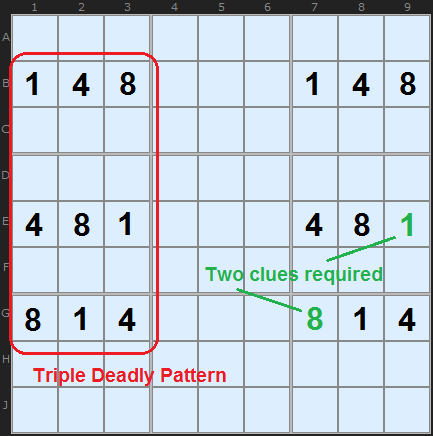

The Deadly Pattern of four cells in exactly two rows, two columns and two boxes can be extended to three rows, three columns and three boxes. This applies to both Unique Rectangle and Avoidable Rectangles.

Consider this set of numbers here. {1,4,8} are solutions in a finished puzzle - the rest of the numbers have been removed. From the point of view of an Avoidable Rectangle the puzzle maker must make at least two of these numbers clues - and two different numbers at that. I've shown in green two example cells that will ensure there is a single solution. If none of these nine cells were clues then the puzzle solver would fine {1,4,8} in all those places and any combination would give a solution. So the puzzle maker is forced to insert at least two clues.